How the International Reserve Currency System Works – and Whether the End of Dollar Hegemony is Imminent

Exploring Economics, 2025

How the International Reserve Currency System Works – and Whether the End of Dollar Hegemony is Imminent

What constitutes the dominance of the US dollar, what it provides for the US and the rest of the world, why it is constantly questioned, and what the future might hold for the dollar

"Every evening I ask myself why all countries must base their trade on the dollar. Why can't we trade based on our own currencies? Who decided it should be the dollar? Today, a country must chase after the dollar just to be able to export."

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, President of Brazil, April 12, 2023

Since the 1960s, politicians have lamented the global dominance of the US dollar, and its demise has been predicted since the early 1970s. Yet it persists – despite massive US trade deficits, rising debt, and the rise of rivals like the euro and the Chinese renminbi. The US currency remains the world's reserve currency, yet criticism of it also endures – criticism that is turning practical: More and more countries are trying to become less dependent on the dollar. The following text attempts to explain what the global currency competition is fundamentally about and what is at stake for whom: What is a "world currency"? What constitutes the dollar's "dominance"? What do the US gain from this dominance? Where does the desire to replace the dollar come from, and why have its competitors – so far – failed?

1. Money as Reified Power

This global competition among currencies – the dollar's stubborn dominance despite all criticism and the unsuccessful yet growing efforts to find alternatives – raises fundamental questions: What is money in this system that its global validity is so fiercely contested? To understand the dynamics of currency competition and the significance of dollar dominance, one must grasp money's role under capitalism. It is not merely a practical medium of exchange, but the driving force of the system itself and a form of power. For money is, at its core, nothing other than reified power – access to societal wealth and command over labor.

Conventional economic theory primarily views money as a neutral transaction medium: It serves as a universal medium of exchange making goods trade more efficient, as a unit of account enabling value comparison, and as a store of value allowing intertemporal planning. This functional perspective, however, reduces money to its technical-instrumental dimension.

In contrast, an analysis rooted in the capitalist mode of production highlights: Money is more than a mere instrument of circulation. It is the necessary starting and end point of the capitalist valorization process. The systemic purpose of production is not supplying goods, but multiplying money capital. This means: When companies invest €100 to acquire means of production and labor, produce, and sell, they do so to get an increased sum of money back at the end, say €110. Money stands at the beginning and the end of this all-decisive capitalist calculation. Making more money from money – that is the engine of the system and the motivation for firms. Everything else is subordinated to the success of this operation: what, when, how, by whom it is produced, and whether it is produced at all. The bottom-line goal is an enlarged sum of value – or: value must have valorized itself. This enlarged sum of value then becomes the starting point for the next round, which should again end with a larger sum of value. This movement is endless and recognizes no measure except: more. This is the root of capitalism's "growth imperative."

By multiplying sums of money, a company or its owners become richer. This means it increases its power over society. For money is precisely this: private power of access to societal wealth, to labor power, to things and people. Money measures this power; it is its independent form – power as a thing, as an objectified social form. Everything is for sale; with money, one can appropriate the world. Money is thus not merely a useful instrument for buying, storing value, or measuring the value of goods. It can only perform these functions if it reliably guarantees power to its holder, if it "holds value." Regarding this validity, there are vast differences in the world.

2. One World, Many Monies: The Currency Hierarchy

Why does a banknote[1] become money? What grants its owner the power to appropriate things? A common explanation is: Whatever is accepted as money in exchange for goods is money. This is correct on one level – what isn't accepted isn't money. But this acceptance of a banknote has a foundation: the state's decree to install its printed products as national money, thereby establishing its validity. National money must be accepted. In Germany, for example, there is generally a legal obligation to accept cash for settling monetary debts[2]. The material basis for society's "acceptance" of the domestic banknote is thus state power.

This, however, initially only applies within national borders. Beyond the border, the state's monopoly on force ends, and other monopolies on force begin, enforcing their own monies[3]. To open up markets beyond their own borders for domestic firms, states agree to mutually recognize each other's monies. They make their monies "convertible," meaning exchangeable. This signifies their recognition of each other's currencies' status as money. For instance, you generally cannot shop in Germany with Polish złoty, nor in Poland with euros. But you can go to a bank and exchange the monies. This is not a given. The prerequisite is the states' agreement to recognize their currencies as money-equivalent. This is expressed in the exchange rate, which contains an equality sign: 1 złoty = 0.25 euros.

Worldwide, there are numerous national currencies, each claiming to be money. The US has the dollar[4], Zambia has the kwacha, Mexico the peso, the UK the pound, Nigeria the naira, and Myanmar the kyat. They can be exchanged against each other – so in mid-May 2025, one dollar was worth 27 kwacha. The equation "1 dollar = 27 kwacha" is, however, theoretical – there can be no talk of equality here. For the Zambian currency is only a means of accessing goods within Zambia. Beyond its borders, economic actors do not accept it, or do so extremely rarely, because it is considered "weak." Anyone trying to exchange kwacha for euros at a bank in Germany will fail.

Other currencies like the euro or US dollar, in contrast, are considered "strong." This is not a question of the exchange rate, i.e., whether euros and dollars appreciate or depreciate. It's a question of their fundamental validity, which in the dollar's case is global. Worldwide, it is accepted as the ultimate expression of value. The dollar thereby measures global wealth – not just goods, but also other monies. Or put differently: One dollar is always worth one dollar. But what 1 kwacha is worth is decided by its exchange rate to the US dollar. It is the benchmark. An investor investing in Zambian copper mines gains nothing from knowing a profit of 50 million kwacha awaits. What this profit is "really" worth depends on how many dollars she gets for 50 million kwacha – how much globally valid payment power 50 million kwacha actually represent. The US money is the ultimate measure of value; all others measure their value in it.[5] Or in other words: Under capitalism, it's about money, and money has its final home in the dollar, which is why it is considered a "safe haven" in times of crisis, where investors flee to save their money.

3. Historical Genesis: How the Dollar Became the Global Power Currency

The dollar's current top position in the global currency hierarchy – as a universally accepted value benchmark and "safe haven" – is not a natural phenomenon. It is the result of a power-political transformation in the 20th century. Its rise to reserve currency occurred amid geopolitical upheavals that displaced the British pound as the previous global reserve currency. Crucial was the US ability to translate its economic and military supremacy after World War II into a new monetary system. This process culminated initially in the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement – formalizing a dollar-gold peg – and paradoxically ended precisely with its termination in the 1971 Nixon Shock. For contrary to all predictions, the dollar proved stable enough to maintain its global dominance even without gold backing. The following briefly reconstructs how this hegemony was established and why it survived the collapse of its own institutional foundation.

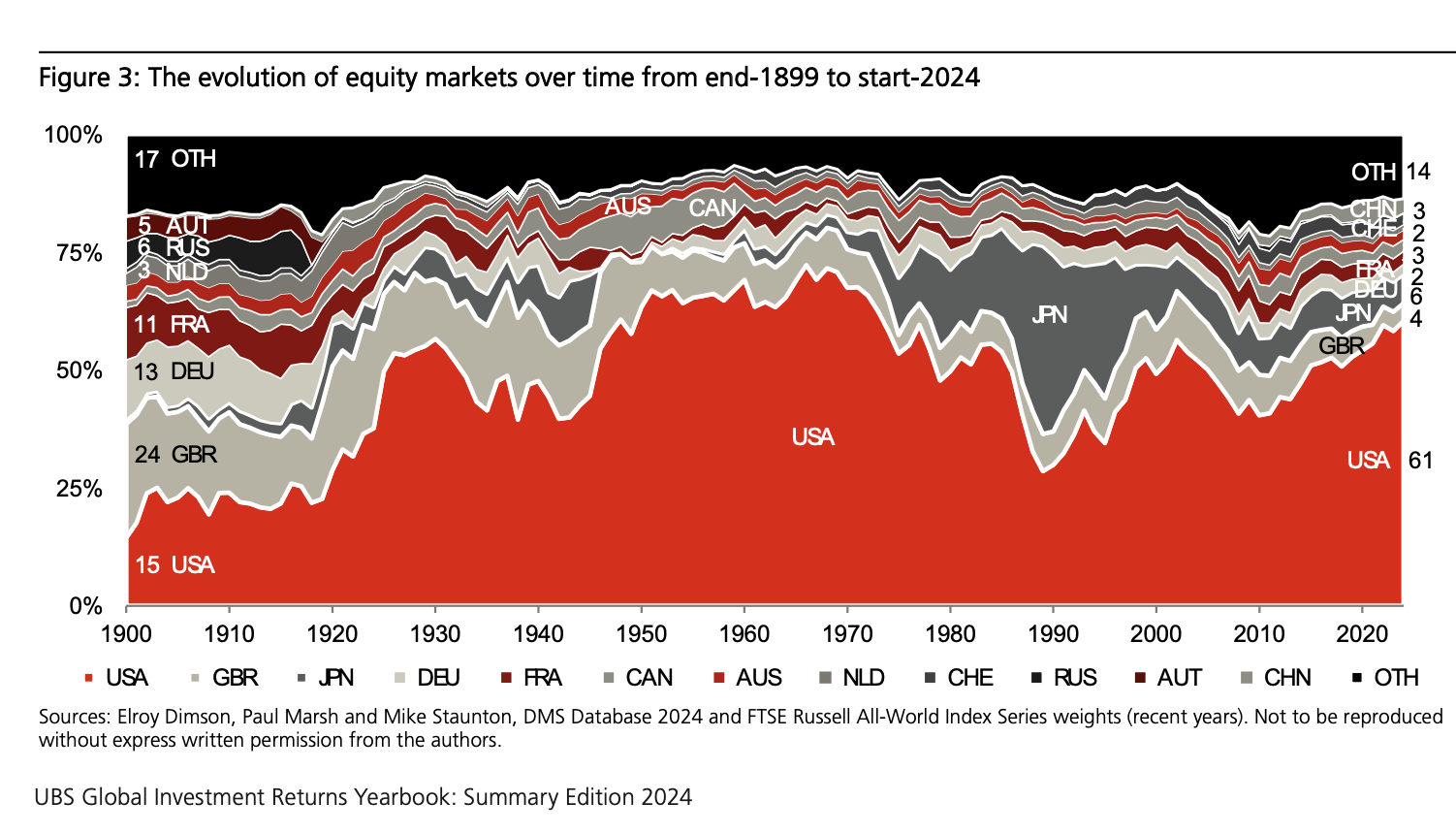

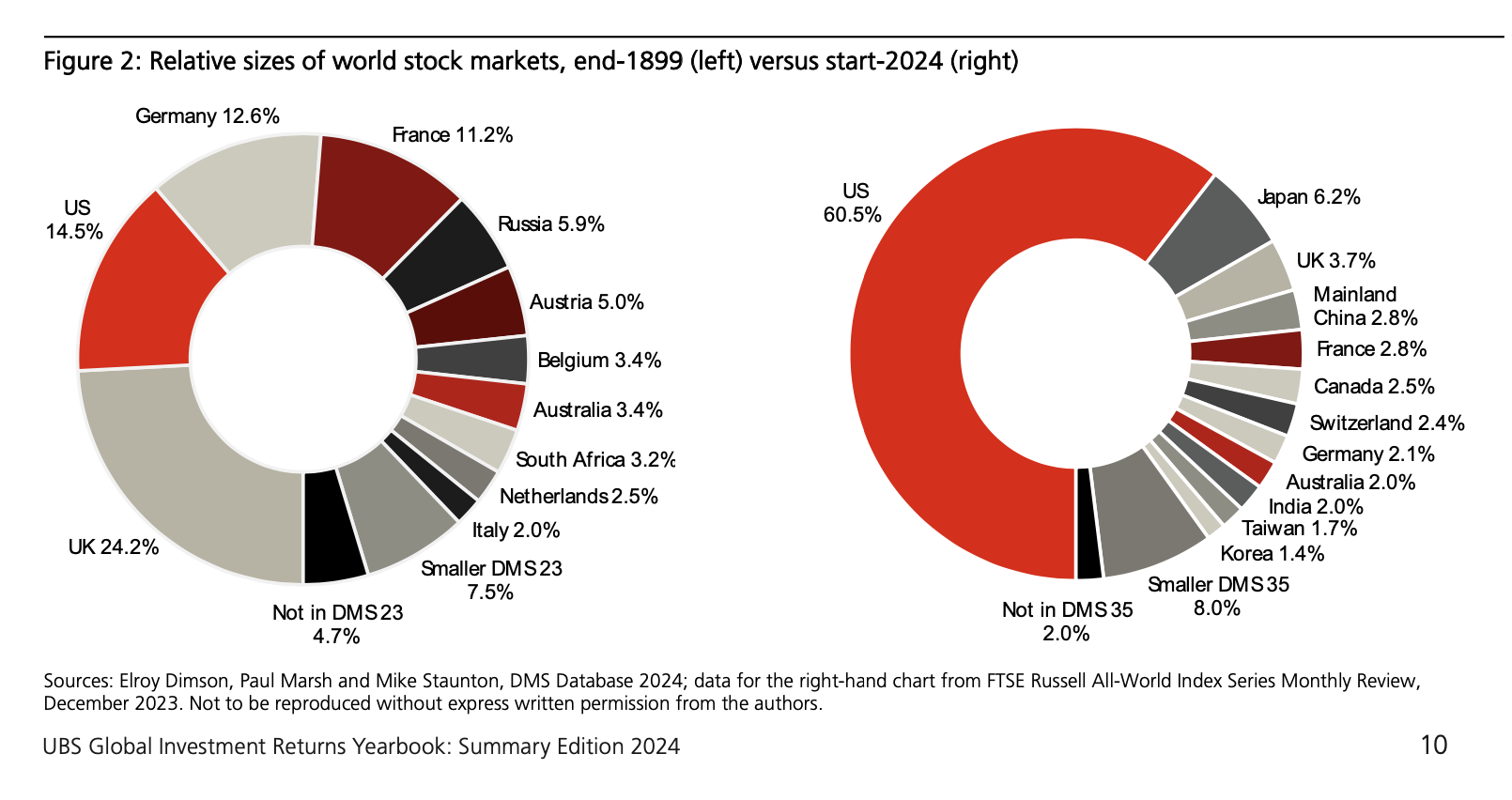

In the 19th century, the United States rose to become a global industrial power – and a financial power. By the early 20th century, the US stock market surpassed its British counterpart in volume.[6]

Following the financial crisis of World War I, the dollar gained importance and definitively replaced the British pound as the world's reserve currency by the end of World War II. At that time, the US was the undisputed world economic power number one; its economic output accounted for about one-third of global GDP. Other major industrial nations had incurred debts to the US during the war, and the largest part of the world's gold reserves was stored at the US Army base in Fort Knox. The capital-rich US corporations set global productivity standards, and its military was overwhelmingly powerful. The economies, and thus the monies, of competing locations, however, were damaged or invalid. In this situation, the US established a new world economic and financial order, forced the dismantling of trade barriers, and thus gradually created a free world market[7].

The institutional basis for the dollar's status was the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement, which also led to the founding of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. Most countries pegged their currencies to the dollar, which served as the anchor of the system. Exchange rates could only be adjusted under specific conditions. In return, the US committed to redeem dollar reserves held by foreign central banks at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce of gold. In short: The link to gold was to guarantee the money-equality of the dollar, and the link of other monies to the dollar was to guarantee their money-equality. This way, Western nations were enabled to participate in international trade. Thus, the world became an export market for the US and a sphere for investing its dollars.

"A primary goal of the Bretton Woods institutions was to promote world trade, which their founders viewed as the key to economic prosperity and a more peaceful world," writes the Peterson Institute[8]. The US approach, however, was not selfless. According to political scientist G. John Ikenberry, the US "recognized that building the international economic order on the basis of coercion would be costly and ultimately counterproductive. This is not to say that the United States did not exercise hegemonic power; it is only to say that there were real limits to the coercive pursuit of the American postwar agenda."[9]

On the newly created world market, it was crucial for economically weakened countries, particularly in Western Europe, to earn dollars by exporting to the US to regain international solvency. The US current account deficits of the 1950s were therefore welcomed to alleviate the initial global dollar shortage. During the post-war boom, industries in Western Europe and Japan experienced an upswing and challenged US industrial competitiveness. The masses of dollars they earned led to a global dollar glut by the 1960s. Loans taken by Washington to finance the Vietnam War also contributed.

The consequence: "The growing dollar overhang meant that by the late 1960s, foreign dollar holdings (nearly $50 billion) far exceeded US gold reserves (about $10 billion). The United States could never have met its obligation to convert gold into dollars if foreign central banks had started demanding gold for all their dollar reserves."[10] This fueled doubts about the US currency. One solution would have been to devalue the dollar against other currencies. But since the dollar was the world reserve currency and the anchor of the international monetary system, other countries could revalue or devalue their currencies against the dollar, but the United States could not devalue the dollar against other currencies. Other countries, in turn, hesitated to revalue their currencies because they didn't want to jeopardize the competitive position of their export industries.

Instead of devaluing their currency, the United States could also have unilaterally devalued the dollar against gold, i.e., raised the dollar's gold price. They long refrained from this, fearing a loss of prestige for the dollar. As a stopgap, Washington restricted imports of certain goods from Europe and Japan in the 1960s to reduce dollar outflows[11]. By the early seventies, however, the situation became untenable: On August 15, 1971, US President Richard Nixon "closed the gold window," ending the ability of foreign central banks to exchange their dollar holdings for gold.

The "Nixon Shock" ended the Bretton Woods system; the dollar lost its gold peg and with it, the entire world monetary system. US economist Charles Kindleberger subsequently declared the dollar 'finished as international money'. "He was clearly wrong."[12] Within 18 turbulent months, the world's major economies began pegging their currencies to the dollar. In subsequent years, a system of flexible exchange rates emerged. Yet within it, the dollar retained its status as reserve currency – a system that persists to this day.

4. The Dollar's Dominance Today: Empirical Evidence

The historical genesis of the dollar as the global reserve currency – from its institutionalized gold peg to its paradoxical stabilization after the Nixon Shock – only partially explains its enduring power. Crucially, this supremacy materializes in concrete hegemonic practices: The dollar dominates not through agreements, but through its ubiquitous functionality in global capital flows. Its position as a "safe haven" and universal value benchmark (see Section 1) manifests empirically in four key areas: as the dominant transaction medium in world trade, as the primary credit and investment currency, as the central reference point for foreign exchange markets, and as the indispensable reserve hoard of state central banks. The following data not only attest to its enduring dominance – they show how the dollar shapes the architecture of global capitalism to this day.

4.1. Transaction Medium

First, the world needs and uses the dollar to buy and trade goods with it. Key reasons for its enduring dominance "include the predominant dollar pricing of commodity trade, particularly the globally significant oil trade, as well as the dollar invoicing of a considerable portion of international goods trade."[13] "Dollar pricing" means commodity prices are set globally in US dollars; "dollar invoicing" refers to the practice of issuing trade invoices in dollars – even when no US firm is involved.

Between 1999 and 2019, the dollar accounted for 96% of trade invoices in North and South America, 74% in the Asia-Pacific region, and 79% in the rest of the world. This means: The US dollar also dominates trade in which the US is not even involved. Take South Korea and Japan: Both have potent currencies; Japan's yen is even a world currency. But for its exports to Japan, South Korea demands payment in dollars 45% of the time, and yen 45% of the time. The remainder is paid in South Korean won and euros. The dollar dominates – except in Europe, where the euro leads with a 66% share.[14]

4.2. Credit Medium, Investment Currency, and Reserve Hoard

Partly due to its dominant role as a medium of exchange, the US dollar is also the prevailing currency in international banking. Around 60% of international and foreign currency-denominated claims (primarily loans) and liabilities (primarily deposits) are denominated in US dollars. This share has remained relatively stable since 2000 and is significantly higher than the euro's (about 20%). The US dollar also dominates the issuance of foreign currency debt securities – securities issued by companies in a currency other than that of their home country. The percentage of foreign currency debt denominated in US dollars has been around 70% since 2010 (euro: 21%).[15]

The diverse sources of demand for US dollars are also reflected in its high share of foreign exchange transactions. The Bank for International Settlements' 2022 Triennial Central Bank Survey shows that the US dollar was bought or sold in nearly 90% of all global foreign exchange transactions in April 2022[16] (total adds to 200% as transactions involve currency pairs). This share has remained stable over the past 20 years. In contrast, the euro was bought or sold in only 31% of transactions.

The systemic dependence on the dollar as the global transaction currency makes the US Federal Reserve (Fed) the de facto world central bank – especially in times of crisis. When a global run on dollar liquidity erupted during the 2008-2009 financial crisis and again during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, payment chains threatened to collapse. The Fed responded by establishing temporary, later permanent, swap lines: credit agreements through which it provided dollars to selected central banks (including ECB, Bank of Japan) in exchange for local currencies. The volumes were enormous: $585 billion in 2009 and $450 billion in 2020.

Parallel swap networks established by other central banks – such as the European Central Bank in euros – were scarcely used in contrast. This asymmetry underscores what economists call the "dollar funding cycle": Since roughly 60% of all international bank claims are dollar-denominated, the Fed becomes the only entity capable of preventing global liquidity crises. This cements a self-reinforcing mechanism: The more the dollar acts as a "safe haven" in crises, the greater the dependence on the Fed as the ultimate liquidity guarantor – and the more entrenched its structural hegemony becomes.

Beyond its central role as a transaction and credit currency, the dollar is also the preferred investment currency and safe haven, as the US boasts especially large and liquid financial markets. Finally, the US bond market is colossal; at $51 trillion, it constitutes 40% of the global bond market. China barely reaches 16%, while Germany, France, and Italy combined account for 8%. Around 60% of global equity capital is listed in the US[17], even though the US share of the world economy is only – depending on calculation – between 15% and 25%.

The status of US money is most evident in the composition of foreign exchange reserves hoarded by central banks worldwide: Nearly 60% consist of dollars, with the euro a distant second at 20%. The rest of the world's monies play virtually no role.[18]

The credit relationship between the US and other countries is also militarily underpinned: According to calculations by US economist Colin Weiss, three-quarters of all official US dollar foreign exchange reserves are held by countries militarily aligned with the US[19]. Washington's largest creditors include Western European states, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Australia, but also India and the Philippines – all countries with a tense relationship with China and thus reliant on US support. "Even if a bloc of states not geopolitically aligned with the US were to decide to reduce their dollar dependence in trade and finance, this would hardly end the dollar's dominance," Weiss states.

Furthermore, many countries acquire US dollars as a store of value to limit fluctuations in their own currencies against the US dollar – in other words, they use it as an anchor currency to stabilize their own money. According to estimates, in 2015 about half of global GDP was generated in countries whose currency was pegged to the US dollar (excluding the US itself). In contrast, the share of global GDP pegged to the euro was only 5% (excluding the Eurozone).[20]

Debts are assets: States hold official foreign exchange reserves as a hoard for emergencies and to underpin their creditworthiness or currency stability. For this, they acquire internationally recognized monies. The US, however, is the only country that barely needs reserves in foreign currencies. Because it produces the globally valid money itself. With it, they can buy and invest globally, incur debts in it, and lend it. For the dollar is desired everywhere.

What states and private entities hoard as dollar reserves consists only to a small extent of paper banknotes. The US central bank estimates that over one trillion US dollar banknotes were held by foreigners at the end of 2022, accounting for about half of the total dollar banknotes in circulation.[21] The bulk of global dollar reserves consists of US Treasury bonds. At the end of 2022, $7.4 trillion, or 31% of outstanding marketable Treasury securities, were held by foreign investors. This means: What private entities and states worldwide hoard as treasure are IOUs of the US, largely from the government. The foreign exchange reserves represent a gigantic loan the world extends to the United States.

5. Dollar Reserve Currency – Foundation of US Global Power

The empirical ubiquity of the dollar – as a trade, credit, and reserve currency – is not self-sustaining; it is an expression of a power structure. At its core, the dollar's elevated position rests firstly on the economic potency of the US – US economic performance not only shows high growth rates over time, it is also very large - depending on calculation, the largest or second largest in the world. This economic potency also includes the US technological leadership, particularly in the digital economy. Secondly, the dollar is an integral part of global business; it is earned, invested, and accumulated beyond US borders. This means: Behind US money stands not only the economic power of the US, but the economic power of large parts of the entire world[22]. Therefore, the dollar is considered a safe haven even when global crises originate in the US.

Secondly, the US is the undisputed world's largest military power. This power is extended through a system of alliances, meaning the US largely controls the political conditions of its global economic success.

The third pillar of the dollar is the enormous US financial market. The volume of available dollar-denominated investments is gigantic and utilized by the entire world. "The US capital market is the linchpin of the global financial system. The highly liquid markets are a capacious reservoir for the investment of global savings."[23]

Each of these pillars of power – economic strength, financial power, military might – secures the US dollar its global dominance, just as, conversely, the global dominance of the dollar strengthens the pillars of US power.

For the US, the dollar's status opens the possibility, firstly, to buy globally in its own currency, thus financing its much-lamented import surpluses, appropriating globally produced wealth. The trade deficit is financed by selling assets or incurring debt abroad – meaning: Foreign investors buy American assets or extend credit to US companies or the state. As the world's safest debtor, Washington receives any credit it needs for its economic, technological, or military programs from global financial markets.

At the end of 2024, foreigners held US stocks or investment fund shares worth $18.4 trillion. Added to this were debt securities, such as US Treasuries, worth $14.6 trillion. Total foreign portfolio investments thus amounted to $33 trillion. This corresponded to 113% of US GDP. In contrast, US investors held only about $16 trillion (54% of US GDP) in portfolio investments abroad. Here, stocks and investment funds ($12.1 trillion) have a significantly larger share than the nearly $3.8 trillion in debt securities.[24]

The world's money thus flows to US capital markets, financing business ideas of private firms. This gives rise to superstar firms like Tesla, Alphabet, or Nvidia. For technological breakthroughs, the United States thus has hundreds of billions available – even US technological superiority rests on the attractiveness of its financial market and thus its currency.

The dollar as the foundation of the gigantic US financial market not only secures virtually endless credit for US companies and banks. The US government also utilizes what French President Giscard d'Estaing once called the "exorbitant privilege" of the US. And extensively so: According to official estimates, US national debt is expected to reach 100% of US economic output in 2025, with a rising trend.

In sum, the US is indebted abroad. This initially poses no problem for them; on the contrary: Although in 2024, $62 trillion in international US liabilities stood against only $33 trillion in US claims on the rest of the world, the US still made a profit: "In 2024, US residents earned $1.5 trillion in income on their international investments, while foreigners earned only $1.4 trillion on their investments in the US. In other words: Americans earned roughly twice the return on their international assets."[25]

The US thus acts quasi as the world's venture capitalist and foremost global creditor. "They attract capital, pay their creditors low interest for it, and invest these inflows into more profitable ventures worldwide."[26] This role "in turn strengthens their privilege, as they can access capital cheaply and channel it into productive investments. And this cycle, in turn, perpetuates their dominance and strengthens their position as key powers in the economic world."

Summarizing this, Bernd Kempa, Professor of International Economics in Münster, concludes: "The reserve currency status of the US dollar brings significant economic advantages for the US. The US central bank, as the issuer of the world currency, realizes considerable seigniorage gains by providing international dollar liquidity, as the use of dollar reserves abroad represents an interest-free loan for the US. Since a large portion of these funds is held abroad in the form of US Treasury securities, the US government can simultaneously refinance itself at significantly lower interest rates than would be possible without the dollar's reserve status. Through this 'exorbitant privilege' as the reserve currency country, the US gains economic profits averaging about three percent of US GDP annually. US companies also realize transaction cost savings through dollar invoicing by eliminating exchange rate risk in international engagements, gaining competitive advantages over foreign rivals."[27]

But the "exorbitant privilege" extends far beyond economic gains: It grants the US unique political power - the world needs the dollar, and Washington uses this power as a political lever: Through financial sanctions, it excludes countries like Russia or Iran from the US capital market and thus large parts of the global financial market. Following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the US and its allies even confiscated the Russian central bank's foreign exchange reserves of about $300 billion held in the West.[28] Simultaneously, Washington can threaten so-called secondary sanctions against countries that do not comply with its sanctions. Because the dollar is the dominant international transaction medium, the US is thus able to enforce its sanctions policy globally.

The dominant position of the US and its dollar also enables the US to conduct comprehensive surveillance of global money flows. They particularly utilize the central position of New York banks in the international payment system, which operates through correspondent banks. A simplified example: If an Iranian company wants to buy a machine in Germany, the payment is processed via the German and Iranian banks. Since not all banks worldwide have direct account relationships, third and fourth banks must be involved as intermediaries[29]. It is practically always possible to find a chain of banks with account relationships. The most important intermediaries in this system are those banks used by many market participants. And these central nodes are the large US banks that finance business worldwide and forward payment orders for credit institutions. They thus possess the necessary information – and must now pass it on to Washington.[30]

"At least since 2009, US banks and their supervising authorities have learned the identity of the ultimate beneficial owner of every single dollar transaction worldwide," explains Commerzbank. "This gives US authorities the ability to enforce sanctions globally – not only against domestic banks, but also foreign ones."[31] For Washington can also threaten European banks with denying them access to the dollar and the US financial system should they fail to comply with US sanctions. And no bank can afford that.

"Only the dollar's status as the world reserve currency gives the US the ability to enforce its sanctions policy worldwide," explains Commerzbank, illustrating this with an example: If Norway's government tried something similar, banks and individuals could easily avoid payments in Norwegian krone. "No bank operating internationally has that choice when it comes to dollar payments – precisely because the US currency is the world reserve currency."[32]

6. The Dollar as Reserve Currency – A Precarious Arrangement

The status of the dollar as the world reserve currency and global money is regularly – and increasingly so recently – called into question. One reason lies in an inherent contradiction of the dollar system: Because the whole world needs and wants dollars, the US must permanently produce dollar-denominated assets like US Treasury bonds, must thus maintain and increase the quantity of globally available dollars, and thereby permanently incur debt abroad. The mirror image of this is huge deficits in both the US federal budget[33] and the US current account[34] – the latter essentially quantifying the fact that the United States imports more than it exports.

The result can be seen in the US International Investment Position (NIIP). The NIIP quantifies the difference between foreign claims on the US and US claims on the rest of the world. The US NIIP showed a deficit of $26 trillion at the end of 2024; the US was thus net indebted to the rest of the world by an amount equivalent to 90% of its economic output[35]. This makes the US the world's largest debtor.[36] Rising US debt thus reflects, on one hand, its freedom to borrow, while on the other, it regularly fuels doubts about its creditworthiness.

The dollar's status as the only true international currency is still supported by several factors – including network effects (everyone uses it because everyone else does), the enormous and open US financial markets, "openness to trade, a strong commitment to the rule of law, and an efficient court system that protects the rights of foreign creditors."[37] But precisely regarding openness and the rule of law, doubts have grown, particularly since Donald Trump's first presidency – and even more since the start of his second term. The US government imposed high import tariffs in early 2025, most likely violating World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. In competition with China, it also enacts export controls and restrictions to limit the export of high technology. Foreign investments in the US are increasingly scrutinized for potential harm to US national security. Moreover, the US is withdrawing from international cooperation on climate protection and human rights. All these measures point, on one hand, to a more aggressive US government stance towards the outside world. On the other hand, they harm the US and its economy, for example by making imports more expensive.

The dollar's attractiveness is further damaged by its use as a sanctions tool: To enforce its foreign policy goals, the US occasionally decouples countries from the US banking system and thus the global dollar flow. Thereby, Washington relativizes the dollar's universality – its general availability. Actions like freezing the Russian central bank's reserves also raise questions in China and other states about the safety of their dollar assets.[38] Reacting to geopolitical moves away from the dollar, Donald Trump reportedly considered penalties in 2024 for countries seeking to decouple from the dollar. These penalties could consist of export bans or tariffs. "I hate it when countries abandon the dollar," Trump said. Should US money lose its global status, "it would be the greatest war we ever lost."[39]

A global reserve currency based on coercion, however, cannot function. This raises the question of an alternative to the dollar. For one is needed to dethrone it. The dollar would only be endangered if a loss of confidence in foreign exchange markets "led to a rapid substitution of dollar holdings into other currencies and threatened the status of the US dollar as the world currency."[40] But this substitution is currently inconceivable. Because there is "no other sufficiently capacious financial market to 're-park' funds in the trillions."[41]

The euro is indeed the second world currency. But the euro market for government bonds is simply too small to absorb global funds. At €11 trillion, it is only about half the size of the US Treasury market. Crucially, however, the euro debt market is not homogeneous. It is spread across 20 member states with differing economic size, credit quality, and political stability. There is a lack of a pan-European "safe asset," a top-tier security with large volume that could compete with US Treasuries[42]. Europe could unify its financial market and create a common European security. This, however, has so far failed due to national divisions – particularly German resistance to a European "debt union."[43] Europe would thus have to overcome its differences to challenge the dollar – and thereby gradually displace it. The question remains how the US would react if one of the cornerstones of its global power began to crumble.

The Chinese renminbi could also become a challenger to the dollar. China's GDP already exceeds that of the US on a purchasing power parity basis and could surpass US GDP nominally in the 2030s. But this may not be enough to overcome the significant obstacles to broader use of the Chinese renminbi. Importantly, the renminbi is not freely convertible, and investor trust in Chinese institutions is relatively low. All these factors make the Chinese renminbi relatively unattractive to international investors.[44] However, Beijing is working intensively to promote the international use of its currency.[45]

For now, the US dollar benefits from its lack of alternatives – which, however, can be a precarious state. For a lack of alternatives is not the same as confidence in a currency. What would happen if this confidence is sustainably undermined by the US government? Commerzbank explains:

"The worst-case scenario – a full-blown balance of payments crisis (essentially an 'emerging market' crisis) – probably doesn't threaten the Americans. They are, after all, essentially indebted abroad in their own currency. An inability to pay due to a lack of capital inflows or the onset of capital outflows is therefore hardly to be expected. Massive reallocations by foreign investors, i.e., a flight from the dollar, are also unlikely due to a lack of alternatives. What seems possible, however, is that foreigners become reluctant to provide the US with new funds on the usual scale. The issuance of government bonds required by persistently high fiscal deficits could only be placed at higher interest rates due to reduced foreign demand."[46]

Higher interest rates, however, would exacerbate the US problem. After all, interest expenses already stand at one trillion dollars per year, three times higher than in 2020.[47] To pay the (higher) interest while debt increases, the US needs the dollar's world reserve currency status, which guarantees it global credit. Any alternative to the dollar system must therefore expect massive resistance from Washington.

7. Multipolar Currency Order Instead of Dollar Dominance?

For now, dollar hegemony holds. After all, the US remains the strongest military and financial power and a huge economy. Above all, there is no realistic alternative to the dollar – competitors like the euro, yen, or renminbi are simply too small; their financial markets cannot absorb the trillions in global investments.

The idea of using some kind of currency basket instead of the dollar as a global benchmark and liquidity source also has little prospect of success. Examples include the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). These are a kind of "artificial currency" the IMF allocates to countries in payment difficulties[48]. Ultimately, however, SDRs are not a currency but a claim on national monies like dollars or euros. The validity of SDRs, as well as the stability of the IMF as a whole, depend on the willingness to cooperate of the IMF's largest shareholder, the US, which holds 17% of voting rights and thus has veto power in all decisions[49]. Replacing the dollar as the world reserve currency with SDRs would require the US to admit that its dollar can no longer fulfill this function.

A world monetary order where several currencies have regional reserve currency status is also conceivable. This, however, would be anything but a stable arrangement. For one, the loss of the dollar's status would massively damage US creditworthiness and lead to a gigantic devaluation of all the dollar trillions worldwide. The US would be forced into harsh austerity, and the rest of the world would feel that a large part of its financial wealth consists of claims on the US. Secondly, the capitalist world would lose its ultimate and central measure of value, leading to permanent uncertainty about how much a sum of money is actually worth. The safe haven would lie in ruins.

For now, the dollar's status as the money of the world guarantees the financial system a certain form of stability, preventing greater turbulence, especially in times of crisis. This is visible in the dollar's function as the "safe haven" for global capital. In times of major and minor shocks, when financial market actors fear for their investments, reallocations occur in favor of the dollar – even if the origin of the uncertainty is found in the US itself. Thus, there were flights into the dollar both in the fall of 2008, when US investment bank Lehman Brothers failed, triggering the global financial crisis, and in March 2023, when Silicon Valley Bank and two other mid-sized US lenders collapsed, raising fears of another banking crisis.[50]

With the erosion of the dollar, the safety net that has so far protected the global financial market would tear. This net also includes the IMF, which prevents larger debt crises with its loans. By mid-2025, about 95 countries were on IMF support, receiving $165 billion. Dollar credit lines from the US Federal Reserve (see section on Fed swaps in Chapter 4.2), which it opens for central banks of other countries to maintain global liquidity, serve the same safety function. Thus, the Fed prevented a global collapse during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 and the COVID crisis of 2020 by providing Europe and Japan with hundreds of billions of dollars. As former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke wrote in his memoirs on the crisis, these lines proved "critical to containing global contagion."[51]

The US needs the dollar, but the world needs it too. Without a "safe haven," global finance capital drifts on the high seas. A multipolar world order would theoretically offer several havens. But what good is that for global investors if these havens are at war with each other, be it a trade war or a military conflict? For these become more likely the more the status of the global reserve currency, the dollar, erodes. Washington is unlikely to allow its currency to be replaced without a fight. This is also shown by the policy of Trump's second administration, which is willing to use all means at its disposal to preserve the hegemony of the US and its dollar. There is an ever-increasing blending of economic, geopolitical, and military measures – from sanctions against China and Russia, tariff threats against countries reluctant to rearm, to military build-up in the Indo-Pacific and questioning NATO defense guarantees for Europe. Questions of world money are questions of force. Even the replacement of the British pound by the US dollar required two world wars.

[1] The transition from precious metals to banknotes is a separate topic and not part of this text.

[2] In Germany, this obligation arises from Section 14(1) sentence 2 of the Bundesbank Act (BbankG), according to which euro banknotes are the sole unlimited legal tender.

[3] This was also the case in Europe before, when the Deutsche Mark was valid in Germany and the Franc in France. The introduction of the euro unified the means of payment – which is also not part of this text.

[4] When this text refers to "dollar," it always means the US currency.

[5] Dollar and kwacha mark the upper and lower ends of the currency hierarchy. Between them are seamless transitions. Some currencies hold less validity, others more, and a few even have world currency status: euro, Japanese yen, British pound, and gradually the Chinese renminbi.

[7] This free world market also meant that, for example, Great Britain had to abandon its system of trade preferences within its colonial empire.

[9] https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c6869/c6869.pdf

[10] https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/us-dollar-on-edge-by-maurice-obstfeld-2025-04

[11] https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w17749/w17749.pdf

[12] https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/us-dollar-on-edge-by-maurice-obstfeld-2025-04

[16] This is because currency exchange, even for world currencies like the euro or yen, is often settled via the dollar. Thus, euros aren't directly exchanged for yen, but rather euros for dollars and then dollars for yen.

[18] https://data.imf.org/en/Dashboards/COFER%20Dashboard

[19] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4256436

[22] This is further evidenced by the fact that banks outside the US hold massive dollar liabilities, which first exceeded the dollar liabilities of US banks in 2003. See page 3 in: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/stablecoins-and-national-security-learning-the-lessons-of-eurodollars/

[23] Commerzbank: USA – wie sicher ist der sichere Hafen? Economic Insight 27.5.2025

[24] Commerzbank: USA – wie sicher ist der sichere Hafen? Economic Insight 27.5.2025

[25] Commerzbank: USA – wie sicher ist der sichere Hafen? Economic Insight 27.5.2025

[30] The ultimate reason for the central role of US banks is naturally the status of the dollar, which is needed everywhere. Truly global banks require guaranteed access to dollars that can be maintained even during crises. And only one institution can provide this crisis-resistant guarantee: the US central bank, to which US banks are tied.

See also: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/stablecoins-and-national-security-learning-the-lessons-of-eurodollars/

[33] https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60870

[34] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BN.CAB.XOKA.CD?locations=US

[35] https://www.bea.gov/data/intl-trade-investment/international-investment-position

[36] Opposite the debtor country USA are creditor countries like Germany and Japan, whose NIIP (Net International Investment Position) in 2024 showed a credit balance against the rest of the world of $3.6 trillion each.

[37] https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/us-dollar-on-edge-by-maurice-obstfeld-2025-04

[38] This problem becomes virulent for the US particularly in the field of digital currencies like stablecoins. These are digital payment instruments pegged to the dollar and fully backed by dollar reserves. With these digital currencies, it's now possible to conduct cross-border money transfers while bypassing the US banking system. This causes the US government to lose its ability to control these money flows. It might therefore attempt to prohibit or combat the use of digital currencies. Simultaneously, however, dollar-linked digital currencies benefit the US because they increase global dollar usage and thus reinforce its universality.

See: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/stablecoins-and-national-security-learning-the-lessons-of-eurodollars/

[41] Commerzbank: USA – wie sicher ist der sichere Hafen? Economic Insight 27.5.2025

[42] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/ny3j24sm/much-more-than-a-market-report-by-enrico-letta.pdf, page 36

[45] https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2024S09/

[46] Commerzbank: USA – wie sicher ist der sichere Hafen? Economic Insight 27.5.2025

[47] https://www.crfb.org/blogs/interest-costs-could-explode-high-rates-and-more-debt

[49] https://www.imf.org/en/About/executive-board/members-quotas

[50] However, amid the US tariff increases in early 2025, the dollar plunged, causing concern in world financial markets over whether the 'safe haven' was still safe.

Licensed under EE Originals